In Short:

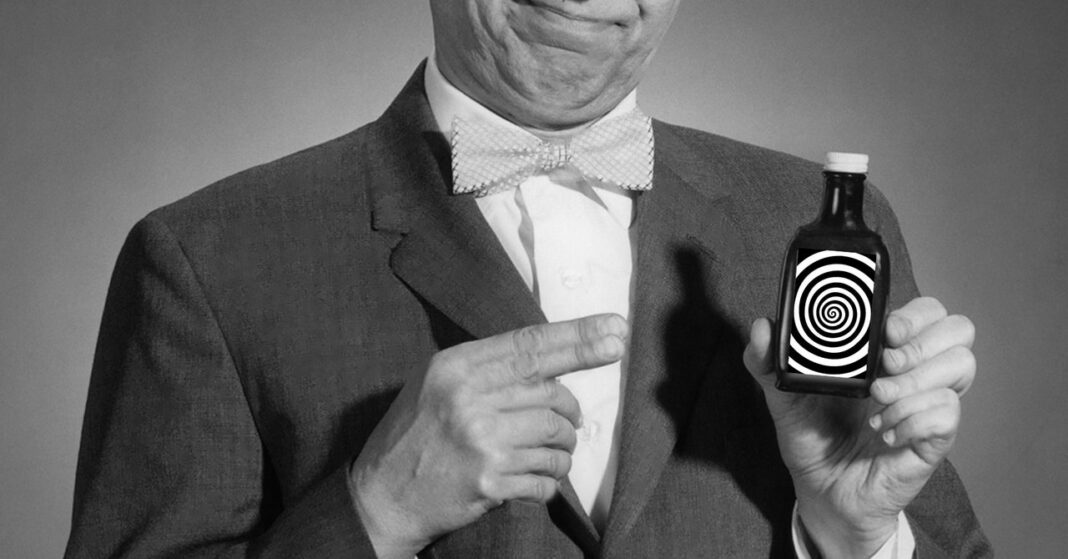

Arvind Narayanan, a Princeton professor, critiques the hype around AI in his Substack, AI Snake Oil, co-written with PhD candidate Sayash Kapoor. Their new book highlights misleading claims from three groups: companies, researchers, and journalists. They emphasize that AI isn’t inherently bad but criticize how it’s portrayed, especially regarding predictive algorithms that can harm marginalized communities and sensationalist media coverage that misrepresents AI capabilities.

Arvind Narayanan, a computer science professor at Princeton University, has gained prominence for his critical analysis of the hype surrounding artificial intelligence through his Substack, AI Snake Oil, co-authored with PhD candidate Sayash Kapoor. Together, they have recently published a book that draws from their acclaimed newsletter, highlighting the shortcomings of AI.

However, it is important to clarify that Narayanan and Kapoor do not oppose the use of new technology. “It’s easy to misconstrue our message as saying that all of AI is harmful or dubious,” Narayanan expressed in a conversation with WIRED. He emphasized that their critiques target the misleading claims propagated by certain entities in the AI landscape, rather than the technology itself.

In their book, AI Snake Oil, the authors identify three primary groups responsible for perpetuating the current hype cycle: companies marketing AI, researchers exploring AI, and journalists reporting on AI.

Hype Super-Spreaders

The authors assert that companies asserting to predict the future through algorithms often represent the most significant potential for fraud. “When predictive AI systems are deployed, the first people they harm are often minorities and those already in poverty,” Narayanan and Kapoor note. They cite an instance in which an algorithm used by a local government in the Netherlands inaccurately targeted women and non-Dutch-speaking immigrants for potential welfare fraud.

Furthermore, Narayanan and Kapoor express skepticism toward companies focused on existential risks, such as artificial general intelligence (AGI). While they do not dismiss the concept, they argue that prioritizing long-term risks often overshadows the immediate harms that current AI technologies impose on individuals, a concern echoed by many researchers.

The authors also attribute much of the prevailing hype and misunderstandings to poor-quality, non-reproducible research. “We found that in a large number of fields, the issue of data leakage leads to overoptimistic claims about how well AI works,” Kapoor explained. Data leakage occurs when AI models are tested using portions of their training data, akin to providing students with the answers prior to an exam.

While academics are described in their work as making “textbook errors,” the authors believe that journalists often exhibit more damaging motivations, knowingly misrepresenting facts. “Many articles are just reworded press releases laundered as news,” assert Narayanan and Kapoor. They highlight the detrimental effects of reporters prioritizing relationship-building with tech companies over honest reporting, which can lead to a toxic media environment.

In response to these criticisms, some journalists reflect on their own practices, recognizing the need to ask tougher questions of AI industry stakeholders. However, this perspective may oversimplify the complex dynamics at play. Even if journalists have access to major AI companies, it does not necessarily prevent them from producing skeptical or investigative reports regarding the technology.

Additionally, sensationalized news stories can distort public perception of AI’s capabilities. Narayanan and Kapoor reference New York Times columnist Kevin Roose’s 2023 chatbot transcript with Microsoft’s tool, titled “Bing’s A.I. Chat: ‘I Want to Be Alive. 😈’.” This example illustrates how journalists can inadvertently contribute to public confusion around the concept of sentient algorithms. Kapoor observes a recurring trend where headlines suggest that chatbots desire to exist, which significantly impacts the public psyche. He compares this phenomenon to the historical case of the ELIZA chatbot from the 1960s, which led users to anthropomorphize a rudimentary AI tool.